In today’s Gospel, Jesus is accused of being a mere man trying to “make himself God”. His opponents got it backwards: Man didn’t become God, but God, in Jesus, became man. That’s another story entirely.

Posts

Once again, this Sunday’s second reading is from 1 Corinthians, and once again it’s from chapter 1 (vv. 10-13, 17). There were real divisions in the congregation that were very worrying to St Paul. Peter Kreeft once noted that Paul was horrified by the beginnings of a sort of “Protestantism” in Corinth. It isn’t a bad analogy at all – many early Protestant movements came to be identified with the particular individual who founded it – Lutheranism (Martin Luther) and Calvinism (John Calvin) are two examples that immediately spring to mind.

In Corinth in the first century, members of the Church were aligning themselves behind various leaders, too. They weren’t leaving the Church per se in order to do that, but these actions still had a very divisive effect. Catholics were forming various “camps” based on which leader they preferred, whether that was Paul, Apollos (a very eloquent preacher in the early Church who had spent some time in Corinth – for more on him see Acts 18:24-28), or Cephas (the Apostle Peter – “Cephas” is “Peter” in Aramaic). Some seemed to reject any merely human leadership, claiming to belong solely to Jesus Christ, without need of any Church intermediaries.

Some representatives of a “parishioner” in Corinth (“Chloe’s people”) had gotten word about this state of affairs to Paul, who at the time was in Ephesus. He was incredulous and extremely disappointed. He thunders, “Is Christ divided? Was Paul crucified for you? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?” He urges them in the strongest words possible (“in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ”) “that all of you agree in what you say, and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and in the same purpose.” Christ must be the centre, and human leaders are only useful inasmuch as they point people not to themselves, but to Jesus.

How can we apply Paul’s warning to us today?

Today, just as in the first century, Catholics are just as tempted to create “cults of personality” centred around human leaders, whether they be bishops, priests, professed religious, or laypeople. There are also people who foolishly believe that they can have full access to Jesus without the Church. How do we deal with such problems? I would suggest two remedies – one for all of us, and one for those in leadership.

First, for all Catholics – we must recognize that the basis of our belief is the one Person of Christ. This is what unites us: “one Lord, one faith, one baptism”, as Paul writes elsewhere (Ephesians 4:3-5). Secondly, leaders must purify their intentions. Why do we do what we do? Is our intention solely to give glory to God, or to ourselves? Humans are always a “mixed bag” of motives to some extent, but our neither our motives nor our message should revolve around ourselves. Paul himself sets the example, as he notes in today’s reading: Christ sent him to “preach the gospel, and not with the wisdom of human eloquence, so that the cross of Christ might not be emptied of its meaning.”

In this Sunday’s Gospel reading (Matt 11:2-11), John the Baptist, who by this time has been imprisoned by Herod, sends messengers to ask Jesus if he is the promised Messiah. Have you ever wondered why John did that? Have you ever wondered why Jesus doesn’t simply answer, “Yes”? Read on!

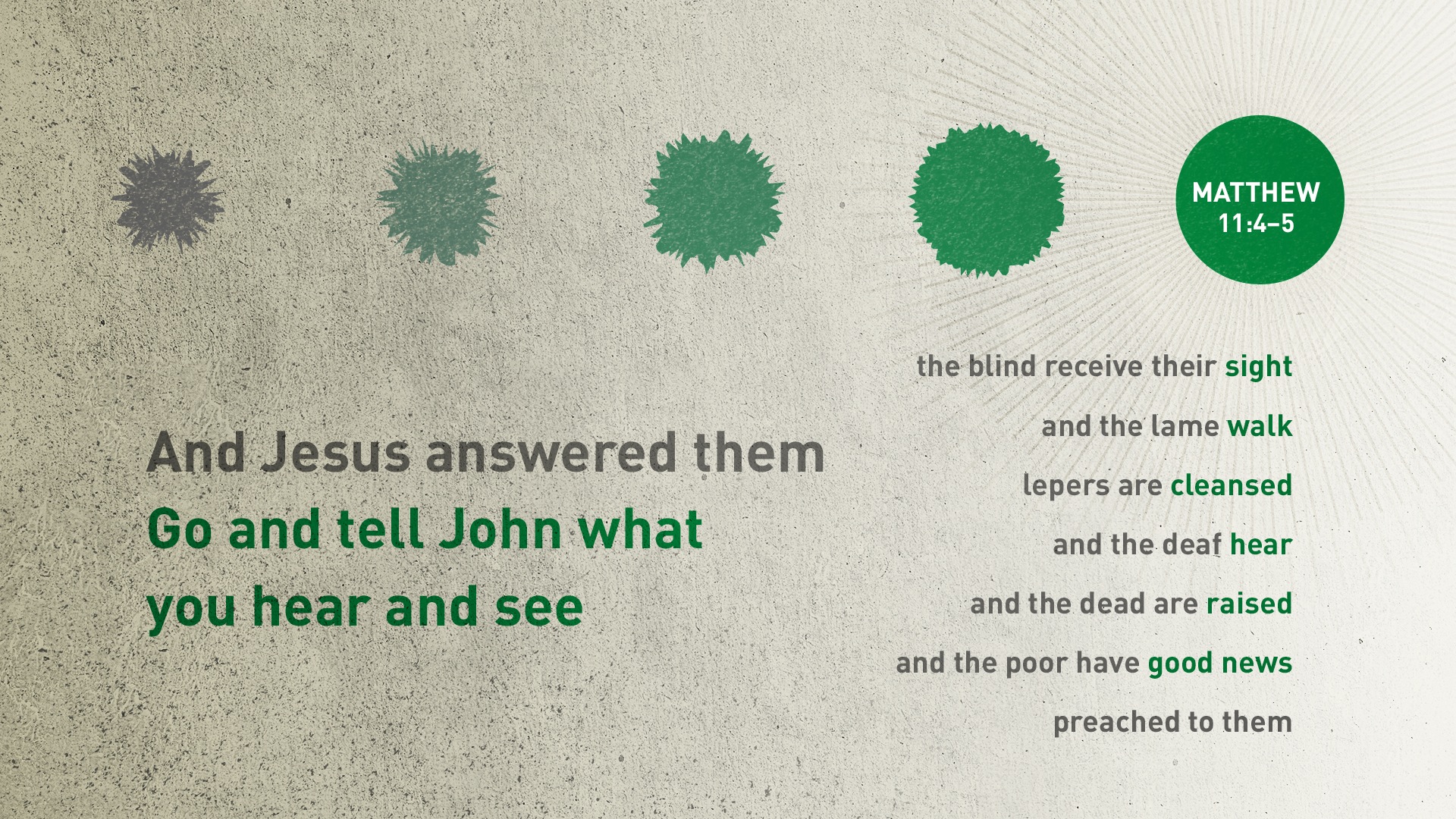

Indeed, Jesus’ reply to the imprisoned John the Baptist (Matt 11:2–6; cf. Luke 7:18–23) is seen by some commentators as not Messianic. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that Jesus never personally believed he was the Messiah. When asked “Are you he who is to come, or shall we look for another?” (Matt 11:3), Jesus answers in what appears to be a vague manner, using words from Isaiah 61: “Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up, and the poor have good news preached to them. And blessed is he who takes no offense at me” (Matt 11:4-6).

A very important clue as to why Jesus answered the way he did was discovered in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Scrolls were written roughly around the time of the Advent of Jesus Christ – between the last three centuries BC and the first century AD. Although they were composed by a sectarian, apocalyptic Jewish sect, they do shed light on what Jews who were roughly contemporaneous to Jesus believed about the coming Messiah.

One of the most important Scrolls that was discovered, known as 4Q521, says this:

For the heavens and the earth will listen to his Messiah…For he will honour the devout upon the throne of eternal royalty, freeing prisoners, giving sight to the blind, straightening out the twisted…and the Lord will perform marvellous acts…for he will heal the badly wounded and will make the dead live, he will proclaim good news to the meek, give lavishly to the needy, lead the exiled, and enrich the hungry.

One can easily see by comparing these two texts why it was that John asked the question about Jesus’ Messiahship, and why Jesus replied the way he did. It was assumed that when the Messiah arrived, according to 4Q521, “prisoners would be set free”. The righteous John, at this time languishing in Herod’s prison fortress at Machaerus, is wondering why Jesus hasn’t sprung him in a “prison break” of sorts. Jesus replies to John by noting that his marvellous works indeed match up with the deeds of the expected Messiah, in line with the teaching of Isaiah 61 and 4Q521. For Jesus to be any more explicit than this would arouse the attention of the secular authorities, prior to the completion of his Messianic mission. However, attentive Jews would have understood Jesus’ claims. Thus, in a culturally relevant manner, Jesus is inviting his fellow Hebrews to consider the evidence of his ministry and draw their own conclusions.

In this Sunday’s Second Reading (33rd Sunday in Ordinary Time), we heard Saint Paul address the Thessalonians:

Brothers and sisters:

You know how one must imitate us.

For we did not act in a disorderly way among you,

nor did we eat food received free from anyone.

On the contrary, in toil and drudgery, night and day

we worked, so as not to burden any of you.

Not that we do not have the right.

Rather, we wanted to present ourselves as a model for you,

so that you might imitate us.

In fact, when we were with you,

we instructed you that if anyone was unwilling to work,

neither should that one eat.

We hear that some are conducting themselves among you in a

disorderly way,

by not keeping busy but minding the business of others.

Such people we instruct and urge in the Lord Jesus Christ to work quietly

and to eat their own food.

– 2 Thessalonians 3:7-12

Saint Paul is extremely forceful and commanding in his instructions to the Thessalonians here – and, by extension, to us. He speaks to both wrongdoers and the congregation as a whole with power: “We command and exhort you…in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ”. This is the strongest language Paul could have used. And what does Paul command? That certain people in the congregation stop being “disorderly” (which is sometimes translated as “idle”).

It’s not necessarily the case that these people were idle in the sense of being inert or slothful – “couch potatoes”, as it were. In fact, it appears they were quite “busy” in their own way – but not in a good way. They were being what Paul calls “busybodies”. That is, they were spending a lot of time and effort “meddling in the affairs of others” – literally, “minding other people’s business”. The so-called “work” that they were doing was not at all productive or helpful for the community. Rather, it was downright disorderly and harmful.

One is reminded of a maxim from Saint Josemaria Escriva:

You are untiring in your activity. But you fail to put order into it, so you do not have as much effect as you should. It reminds me of something I heard once from a very authoritative source. I happened to praise a subordinate in front of his superior. I said, “How hard he works!” “You ought to say”, I was told, “ ‘How much he rushes around!’”

You are untiring in your activity, but it is all fruitless…How much you rush around!

– Furrow, 506

Mere “busyness” can actually be a hidden form of laziness and love of comfort, not to mention disorderliness. Sure, a person can be running around, doing a whole bunch of “stuff” – but they are not the things the person ought to be doing.

There is also the very real temptation of being a “busybody” in another sense – that of being a gossip. This has always been a temptation whenever and wherever people live together, but it is a constant temptation in parish life – for both clergy and laity. As disciples of Jesus Christ, we simply must stop speaking about others behind their backs.

Saint Paul set the Church a powerful example in this regard, by doing hard, constructive, and productive work (in his case, as a tentmaker). He provided for his own needs, and even those of others, so that he was not dependent on anyone else (cf. 1 Thess. 4:11-12). Although, as an apostle, Paul could have received his living from the congregation, he chose not to. He did this so that he could provide a model for how his disciples should live in the world as Christians.

Saint Paul shows that work well done for God’s glory in any honest profession is the “hinge” of our sanctification in the world. We can sanctify our work, we can sanctify ourselves through our work, and we can also sanctify others through our work.

“Sunday Scriptures” is a series of posts explaining the Sunday Mass readings – helpful for those preparing to worship, or preparing a homily!

In this Sunday’s Gospel reading, we hear Jesus’ famous parable about the Pharisee and the tax collector:

Jesus addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else. “Two people went up to the temple area to pray; one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector. The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, ‘O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity — greedy, dishonest, adulterous — or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income.’ But the tax collector stood off at a distance and would not even raise his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast and prayed, ‘O God, be merciful to me a sinner.’ I tell you, the latter went home justified, not the former; for whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.”

– Luke 18:9-14

The mistake of the Pharisee is not found in his avoidance of sin or in his religious observances, like fasting and tithing. In fact, this is all quite laudatory. His real problem lies in his exalted view of himself. He does not discern his own sinfulness or need of God’s forgiveness. The tax collector, on the other hand, does realize that he is a sinner who stands in need of God’s forgiveness – and moreover, that he does not deserve that mercy.

The Pharisee does not realize that, far from being acceptable to God, he is actually an idolater! What the Pharisee is doing, ultimately, is arrogating one of God’s prerogatives unto himself (this is in fact what the devil does, as scholar Charles Talbert points out) – in this case, the prerogative of judgment. The Pharisee, who says, in essence – “I am not a thief” – is actually stealing something from God.

Now, while it is true that we must judge objective actions as being sinful or not, one can never judge a person’s intentions (what their motives may have been) or ultimate destiny (whether they will end up in either Heaven or Hell) before God.

What the Pharisee did not realize was that the tax collector not only a) knew he was a sinner; but b) had already inwardly repented and asked for God’s mercy. Ironically, the hated tax collector, despised by the Pharisee, is accepted by God. The Pharisee, conversely, demonstrates an attitude that God despises. The self-congratulating Pharisee was not aware of his own sin and thus didn’t feel the need to repent. Not having asked God for forgiveness, he therefore wasn’t forgiven! It was actually the tax collector who “went home justified before God”.

Christians should take note of Jesus’ words by practicing personal humility before God and others, and avoiding haughtiness.

“Sunday Scriptures” is a series of posts explaining the Sunday Mass readings – helpful for those preparing to worship, or preparing a homily!

“Sunday Scriptures” is a series of posts explaining the Sunday Mass readings – helpful for those preparing to worship, or preparing a homily!

What does the Church mean when she says that the Bible is the “inspired” Word of God?

In this Sunday’s second reading, we read the following, as Saint Paul writes to his young protege, the bishop Timothy:

Remain faithful to what you have learned and believed, because you know from whom you learned it, and that from infancy you have known the sacred Scriptures, which are capable of giving you wisdom for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that one who belongs to God may be competent, equipped for every good work.

I charge you in the presence of God and of Christ Jesus, who will judge the living and the dead, and by his appearing and his kingly power: proclaim the word; be persistent whether it is convenient or inconvenient; convince, reprimand, encourage, through all patience and teaching.

– 2 Timothy 3:14-4:2

The important phrase to note is: “All Scripture is inspired by God”. The New Testament was, of course, originally written in Greek. The Greek word that is translated as “inspired” in our English new Testament is the word theopneustos. This word, in turn, is really made up of two other words: Theos, which means “God”, and pneu, which means “to breathe”. Thus, theopneustos literally means, “God-breathed”, and this is what is meant by the English word “inspired”.

In the first book of the Bible, we read that God “breathed” his life into Adam (Genesis 2:7), making him a “living soul”. This gave Adam participation in God’s life. This is related to Scripture, because divine inspiration is very much like divine respiration in Adam’s case – what is very human becomes filled with the life of God. The human words of the Bible are filled with the life and message of God.

Further, the word for “breath” in Hebrew (ruah) is the same word used for God’s Holy Spirit. When we are dealing with the “God-breathed” (inspired) Word of God, that means that God the Holy Spirit is the principal author of Scripture. The human beings who actually wrote the 73 books that collectively make up the Scriptures are called the instrumental authors of Scripture (Saint Paul, for example). They were the means, the instruments God used. These authors did not go into a trance when they wrote. They used their personal freedom, intelligence, education, cultural background, and personalities when they composed the sacred Scriptures. But God superintended the process in a providential manner, ensuring that what he wanted to communicate to us in human language made it into the Bible.

Q. This Sunday’s Gospel is taken from John 21. Does this chapter have any implications for the papacy?

A. Other texts, like Matthew 16, are often cited in this regard, but John 21 has one of the strongest proofs for the ongoing role of the office of Peter in the universal Church. Even non-Catholic scholars recognize this.

Q. Does the miraculous catch of fish in this chapter have anything to do with the Petrine office?

A. Fishing, of course, wasn’t just the former trade of the apostles; it represents their evangelistic mission of being “fishers of men”. The unbroken net conveys the unity of the one Catholic (universal) Church. Elsewhere, when Jesus provides a miraculous draught of fish, the nets begin to break from the strain; here, the nets are intact. Peter, dragging the net ashore, evokes his leadership in bringing the Church safely home to Christ, even to the shores of Heaven itself.

Interestingly, although the catch was so big that the disciples struggled to bring the nets aboard, almost sinking their boat, Peter now easily drags the net ashore all by himself. The Greek verb in the original text that is used to describe Peter’s dragging of the net is the same one used by Jesus in John 12:32. This is where Jesus says that, as he is lifted up from the earth, he will draw all people to himself.

Q. Why does the text mention specifically that 153 fish were caught?

A. By far, the most puzzling aspect of the passage is the reference to the 153 fish. First of all, this is an authentic eyewitness detail. On a secondary level, many commentators have proffered various theories to explain what this number might symbolize (John’s Gospel functions on “two levels” – there is often a secondary, “heavenly” meaning to earthly events). Most of these interpretations suggest the idea of the universality or completeness of the catch.

So, to sum up: we have Peter, alone, dragging the unbroken net of a universal catch to the shores of heaven. This is clearly a reference to his position as leader of the Church on earth.

When you add to all of this the threefold charge of Jesus to Peter (“Feed my Sheep”) that immediately follows, the picture is complete. Peter is singularly (in the original Greek text) given this responsibility to shepherd the universal Church. Keep in mind also that this event is recounted in the same Gospel in which Jesus describes himself as the “Good Shepherd” (John 10). Before his Ascension, Jesus here reaffirms Peter’s unique leadership position, passing the earthly reins of the Church to him.

Q. Today’s readings have a common theme: the absolute need to repent of sin, but also God’s abundant mercy for those who do. Would you agree?

A. That’s true. Psalm 103, the Responsorial Psalm from today’s readings, reminds us that “The Lord is kind and merciful”. One of the greatest mercies God provides for us is to “tell it like it is” – to explain reality to us, and warn us of the consequences of not repenting.

This is why St. Paul, in the second reading from 1 Corinthians 10, speaks about members of the Old Testament people of God who did not make it from Egypt to the promised land of Israel. Tragically, these people were “struck down” in the desert because they were not pleasing to the Lord. This was despite the fact that “all of them were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea. All ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink, for they drank from a spiritual rock that followed them, and the rock was the Christ.”

Q. How does this apply to Catholics today?

A. The same dangers and consequences of unrepentance face the modern-day people of God. Like the Israelites of the Exodus generation, Catholics can sometimes view their baptism as a sort of “lifetime membership card” for Heaven. They frequent the communion lines, but not the queue for the confessional. They “all eat the same spiritual food, and all drink the same spiritual drink – the Christ” in the Eucharist. But they run the same risk that the Israelites did – of being “struck down” in the journey through the wilderness of this life, and not making it to the true promised land of Heaven. The reason is that they feel no need to repent of their sin. Just being “Catholic in name only”, they feel, will be enough to get them “in”. But God is not mocked.

Q. How can we avoid this trap?

A. By sincere repentance, and producing the fruit of the Kingdom in their lives. God will always forgive the one who truly is sorry for their sin, and who desires to change. This is why Jesus reminds us that “God is no respecter of persons”. This means that he judges everyone by the same, objective standard. As Jesus said in today’s Gospel, speaking of people who had died tragically in his time, “unless you repent, you will all perish as they did”.

Jesus then tells a parable about a fruitless fig tree. The owner wants to cut it down, but the “gardener”, who represents Christ, pleads with him to give him more time to “fertilize” it. After one more year, if the tree is still fruitless, the owner can cut it down.

We are like those trees. Christ has given us all the “fertilizer” we need to grow and bear fruit that will last. The scriptures, the sacraments, the teaching of the Church, the community of faith – all the conditions necessary for growth. We never know how much time we have left before we face eternity. Let us not waste this Lent. Who knows? It may be the last one we ever have. Let us truly repent and produce the fruit of the Kingdom in our lives, that we may share in the joy of the resurrection harvest.

Q: In this Sunday’s Gospel, Jesus appears to be talking about the end of the world. Is he?

A: There is a real connection with what Jesus is saying here in Mark 13, and with the Book of Revelation, which we are studying on Thursdays here at St Justin’s – you’re welcome to join us! Jesus’ “eschatological discourse” on the end of the universe indeed has reference to the end of history, and the renewal of the space-time universe in which we live. But its most immediate meaning refers to the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple in the year 70 AD.

Remember, Jesus says “Amen, I say to you, this generation will not pass away

until all these things have taken place.” How long is a generation? 40 years. Let’s do some quick math: Jesus’ death and Resurrection took place in approximately 30 AD. Jerusalem and its temple were destroyed exactly 40 years later, in 70 AD. So, Jesus’ solemn prophecy came true. Should anyone be surprised?

Q: What does the destruction of Jerusalem’s temple have to do with the end of the universe?

A: To the Jews, the temple was a miniature model of the universe, and the universe was to them, as it were, a gigantic temple. The temple curtain separating the Holy Place from the Most Holy Place had images of the stars, the moon, and the planets. Thus, when it fell, it was like Jesus predicted: “the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from the sky”.

God’s judgment fell on the wicked temple establishment in 70 AD because of its rejection of the Messiah, as well as because of its avaricious, self-serving leadership. This was indeed the point of last Sunday’s Gospel reading from Mark 12 (the widow’s offering). Almost every preacher uses that text as an example of trust in God and sacrificial giving on the poor widow’s part – and that is undoubtedly a good application of the text.

But, read in context, it is a living parable of what Jesus had just explained about the religious leaders of his day. Jesus had said: “Beware of the scribes, who like to go about in long robes, and to have salutations in the market places and the best seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at feasts, who devour widows’ houses and for a pretense make long prayers. They will receive the greater condemnation.” And he sat down opposite the treasury, and watched the multitude putting money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. And a poor widow came, and put in two copper coins, which make a penny. And he called his disciples to him, and said to them, “Truly, I say to you, this poor widow has put in more than all those who are contributing to the treasury. For they all contributed out of their abundance; but she out of her poverty has put in everything she had, her whole living.” (Mark 12:38-44).

The religious leaders of Jerusalem were supposed to be caring for widows and orphans. Instead, they were “devouring widows’ houses”. And here we have a widow whose house is indeed “devoured”. The two small copper coins she had put into the offering represented, in a sense, her last meal – they were just enough money to buy flour to make one small loaf or cake. In a sense, this woman’s plight was a living illustration of what Jesus had been complaining about.

The ill-treatment of those who were to be cared for and the rejection of Jesus as Messiah were characteristic of an evil temple leadership whose hearts had been closed to God and others. This is why Jesus wept over the city of Jerusalem: he foresaw its destruction because many would fail to repent. May our own hearts learn the lesson well.

Today is the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary, celebrating that God raised the Virgin Mary, body and soul, to the glories of heaven at the end of her earthly journey. Here are four quick facts about this teaching of the Church :

Today is the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary, celebrating that God raised the Virgin Mary, body and soul, to the glories of heaven at the end of her earthly journey. Here are four quick facts about this teaching of the Church :

1. Catholics must believe this in order to hold the Faith.

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian Dogmas (infallible teachings) that Catholics must believe (the others being the Immaculate Conception, Divine Maternity, and Perpetual Virginity of our Lady). The reason why validity of the doctrine can be trusted is that it rests on the same foundation as that of Transubstantiation or the Canon of the Bible – namely, the teaching authority of the Catholic Church.

2. There is good circumstantial, supporting evidence for the Assumption.

No Christian community has ever claimed to have the relics (bones or other mortal remains) of the Virgin Mary. When one considers how Christians venerated the relics and final resting places of important saints in the early Church period (such as St Peter’s Basilica being built over his tomb), it is remarkable that no church has ever claimed to have her relics. If the relics of the Mother of Jesus relics really did exist, they would have been prized above all others. An argument from silence isn’t always the greatest, but in this case, silence speaks volumes.

3. There is indirect, biblical support for the doctrine.

The simple fact of the matter is that, in salvation history recorded in the Bible, “assumptions happen”. Genesis speaks of Enoch, who “walked with God and was no more, because God took him” (Genesis 5:24; cf. Hebrews 11:5). Most interpreters believe that Enoch was assumed, body and soul, into heaven. Also, Elijah was taken up to heaven, body and soul, in a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2:11).

If these holy ones of old could be translated directly to heaven, why not the “Panagia” (“All-Holy”) mother of God, who “gave the Word flesh” (cf. John 1:14)? In Revelation 12, John sees the “Ark of the (New) Covenant”, Mary in heaven.

4. Christians have believed this for centuries.

Catholics did not “invent” the doctrine of the Assumption when Pope Pius XII officially defined it in 1950. All the Pope was doing was making clear that this teaching was always true and part of the deposit of faith (Jude 3) for centuries. How do we know this? Because the Church’s liturgy (including the content of liturgical prayers and feast days) included the Assumption from the earliest times. Some even believe it was the earliest of Marian feast days, originating in Jerusalem.

Many Christian practices were suppressed under the wicked reign of Emperor Hadrian, who had levelled much of Jerusalem in 135 AD, renaming the town after the pagan god Jupiter. After Constantine’s acceptance of the faith in the fourth century, many Christian feasts were revived. The Assumption began to be celebrated in Rome as early as the seventh century. It is in the liturgy that Sacred Tradition is taught most clearly, for “the Church believes as She prays” (Lex orandi, lex credendi).

We have a powerful intercessor in heaven in Mary, who precedes all of us who look forward to life in the new heaven and the new earth in a glorified humanity of body and soul. We close with a liturgical prayer asking for that intercession: Recordare, Virgo Mater Dei, dum steteris in conspectu Domini; ut loquaris pro nobis bona (“Remember, Virgin Mother of God, when you walk in the presence of the Lord, to speak well of us”).