This is my latest piece for Catholic Answers. Have a Blessed Triduum and a very Happy and Holy Easter!

During this sacred Triduum and during Easter, as we commemorate Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection, it is not unusual for us to come across challenges—online, through the media, in our conversations with unbelievers—to the historical truth of these salvific events.

One criticism commonly leveled at the biblical record has to do with Jesus’ prophecies concerning his brutal death.

Skeptics allege that these are a case of prophecy ex eventu—prophecy after the fact. According to some critics, Jesus never really predicted such things. Rather, the early Church, in composing the Gospels, simply put these words in the mouth of our Lord afterward, making his “predictions” match what already happened.

There are, however, a number of compelling reasons to believe that Jesus did truly predict that he would be killed. But before we discuss these, a couple of housekeeping items are in order:

First, due to space constraints, we will only deal with Jesus’ prophecies concerning his death; though a treatment of his predictions concerning his resurrection is of equal value, it will have to wait for another day.

Also, we’ll leave aside the somewhat obvious fact that, as God incarnate, Jesus would have known the future. Those of us who already believe in Christ’s divinity won’t need much convincing on that front, so we’ll focus here on arguments that a skeptic might find plausible.

For the same reason, although Christians believe the Bible to be the infallible and inerrant word of God, we will look at the texts in question as a skeptic might assess any religious text purporting to be of a historical nature.

In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus makes three predictions (which are paralleled in Matthew and Luke) concerning his fate, the first of which is found in Mark 8:31-35:

And he began to teach them that the Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. And he said this plainly. And Peter took him, and began to rebuke him. But turning and seeing his disciples, he rebuked Peter, and said, “Get behind me, Satan! For you are not on the side of God, but of men.” And he called to him the multitude with his disciples, and said to them, “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it” (RSV2CE; the other two instances are found in Mark 9:31 and 10:33-34).

When historical-Jesus scholars examine the Gospels, one of the criteria they use for determining authenticity is called the “criterion of embarrassment.” If something in the text is a potential source of embarrassment for Jesus or for the early Church, there is a greater probability that it is an authentic reminiscence.

There are a number of potential sources of embarrassment in this passage: Peter, the leader of the early Church, is seen to be rebuking his Master. Jesus, in turn, has to rebuke Peter! This could potentially undermine Peter’s authority in the Church. If, as some scholars believe, Peter is the main source of historical material in Mark’s Gospel, this also speaks to the great humility of Peter, who would have related this account at great potential embarrassment to himself.

There is another potentially embarrassing thing to consider. Not only does Jesus predict his own death, but he expects his own disciples to “follow” him in carrying the cross. And yet, as scholar Craig Evans points out, Jesus was unable to do what he asked his own followers to do. In Mark, as in all three synoptic Gospels, someone else (Simon of Cyrene) carried Jesus’ cross (Mark 15:21). It is thus highly unlikely that Mark would have “invented” either the saying or what Simon did—especially considering that Simon’s sons, Alexander and Rufus, were likely members of the church in Rome, to which Mark probably addressed his Gospel (Mark 15:21; Rom 16:13 specifically mentions Rufus), and could corroborate the account.

One obvious—and ominous—portent of Jesus’ own fate was what happened to his relative and forerunner, John the Baptist. Jesus affirmed John’s message of repentance in preparation for the coming kingdom of God, a message that ultimately led to John’s demise. Jesus clearly would have known that by affirming John as a prophet and by continuing in the same vein of teaching as John, he ran the risk of suffering John’s fate. Jesus even sends a message to John’s executioner, Herod Antipas, referencing Jesus’ own impending death:

At that very hour some Pharisees came, and said to him, “Get away from here, for Herod wants to kill you” [showing that not all Pharisees opposed Jesus!]. And he said to them, “Go and tell that fox, ‘Behold, I cast out demons and perform cures today and tomorrow, and the third day I finish my course. Nevertheless I must go on my way today and tomorrow and the day following; for it cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem’” (Luke 13:31-33).

After arriving in Jerusalem and teaching about John in the temple precincts, Jesus tells the parable of the wicked vineyard tenants (Mark 12:1-12), in which Jesus clearly identifies himself with the “beloved son” who is killed. This is yet another piece of the puzzle. But perhaps the clearest piece of evidence that Jesus expected to be killed was something he said shortly before he was arrested.

In the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus “began to be greatly distressed and troubled.” With his soul “sorrowful,” he prays that his hour might pass him by (Mark 14:33-36). That Jesus was “greatly distressed” and prayed to avoid his imminent suffering falls, once again, under the criterion of embarrassment. It is highly unlikely that a Christian would invent such a saying.

Much more could be said, but given these evidences, we already have very good warrant to believe that, in all likelihood, Jesus truly prophesied his passion. He knew, and he wanted his disciples to know, that his earthly mission was to culminate in the events of the Triduum that we will observe this week.

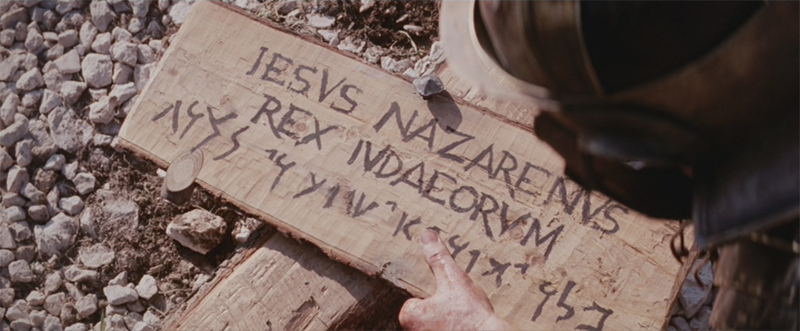

This Sunday, we celebrate the Solemnity of Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. This Sunday also marks the end of the liturgical year. In today’s Gospel (Luke 23:35-43), we read about the crucifixion of Jesus. Speaking of Jesus’ kingship, Luke here mentions the titulus (Latin for “title”, referring here to the the inscription above Jesus’ cross) that read, “This is the King of the Jews”.

This Sunday, we celebrate the Solemnity of Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. This Sunday also marks the end of the liturgical year. In today’s Gospel (Luke 23:35-43), we read about the crucifixion of Jesus. Speaking of Jesus’ kingship, Luke here mentions the titulus (Latin for “title”, referring here to the the inscription above Jesus’ cross) that read, “This is the King of the Jews”.