The scene was a McDonald’s in the aptly named town of Normal, Illinois. I was a 21-year-old business student who was doing an internship at Illinois State University. I was having a chat with Jerry McCorkle, a young adult pastor from a local Baptist Church. And I was in the process of leaving the Catholic Church to become an Evangelical. Over Big Macs, Jerry seemed to give me another big theological reason to make the move. “The Catholic Church invented the Assumption of Mary in the year 1950″, Jerry said. “1950! That’s almost two thousand years after the time of Christ! I mean, where are they coming up with this stuff?” Sadly, I didn’t even know what the Assumption was – such was the state of my Catholic formation at the time. I just nodded my head in silence. Jerry and I had two things in common that day: we were both sincere seekers of God, and neither one of us had any clue what Catholics really believed about the Assumption of Mary. Since today, August 15, is that great solemnity, it’s a good chance to run over some facets of this dogma.

The scene was a McDonald’s in the aptly named town of Normal, Illinois. I was a 21-year-old business student who was doing an internship at Illinois State University. I was having a chat with Jerry McCorkle, a young adult pastor from a local Baptist Church. And I was in the process of leaving the Catholic Church to become an Evangelical. Over Big Macs, Jerry seemed to give me another big theological reason to make the move. “The Catholic Church invented the Assumption of Mary in the year 1950″, Jerry said. “1950! That’s almost two thousand years after the time of Christ! I mean, where are they coming up with this stuff?” Sadly, I didn’t even know what the Assumption was – such was the state of my Catholic formation at the time. I just nodded my head in silence. Jerry and I had two things in common that day: we were both sincere seekers of God, and neither one of us had any clue what Catholics really believed about the Assumption of Mary. Since today, August 15, is that great solemnity, it’s a good chance to run over some facets of this dogma.

The Assumption of Mary is the belief that, at the end of her earthly journey, God took Mary, body and soul, into the glories of heaven. Critics of the Assumption point out that the New Testament never mentions such an event. But not all of the truths of the faith that we need to believe are explicitly recorded in Sacred Scripture – in the Catholic Church we also have the Word of God delivered to us by means of Sacred Tradition – and even Sacred Scripture itself was Sacred Tradition before it was written down. It is also highly likely that Mary was still alive on earth when many, if not all, of the books of the New Testament were being written. Luke, for example, seems to have interviewed Mary himself in writing his gospel, in order to ascertain certain details about the events surrounding the Nativity of Christ.

It is also worth pointing out that all Christians – Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant – believe that Assumptions not only can happen, but have happened! Scripture records for us the case of Enoch, who “was taken up so that he did not see death, and he was not to be found because God took him up. For before his removal he had been commended as having pleased God” (Hebrews 11:5). The prophet Elijah was also taken, or assumed, into heaven – body and soul – by a chariot of fire and a windstorm ( Kings 2).

As Scott Hahn points out in his excellent book, Hail, Holy Queen, no city ever claimed to have the relics of Mary – an absolutely astonishing fact, because the early Christians took great pride in venerating the relics of saints and martyrs, building their altars, and, indeed, their churches upon them. The example of Saint Peter’s Basilica, with its high altar directly over the underground crypt of Peter, is a prime example. The fact that no one ever claimed Mary’s relics, which would have been the ultimate prize, is good corroborating evidence that no one had them, because they didn’t exist. She had already been bodily Assumed into heaven. Two cities (Ephesus and Jerusalem) did claimto be the locale of her tomb, found to be empty, but none claimed the relics.

The liturgy is the place where Sacred Tradition is taught most clearly; the ancient maxim “Lex credendi, Lex orandi” – “the law of belief is the law of prayer”, or “the Church believes as she prays” holds true. If you want to know what Christians really believe, observe how they worship. Just because Pope Pius XII formally defined the dogma of the Assumption in 1950 doesn’t mean that he invented it, as Jerry supposed, or that Catholics didn’t believe it beforehand. A defined dogma of the Church has always been contained in the original deposit of faith, but dogmas can be defined much later, when the need (eg. a heresy challenging the belief) arises. For example, God was always a Trinity of Persons, long before the Council of Nicea affirmed it in the 4th century AD – in fact, this truth goes back to all eternity! But it was never formally defined until it was challenged by the arch-heritic Arius and his followers. The Church clebrated the Assumption in its liturgy – the highest form of prayer, and thus belief – going back to at least the 4th and 5th centuries.

Much more could be said, but it’s fitting that we finish with an argument from what is called “fittingness”. The preface to the Eucharistic prayer for the solemnity reminds us that the Assumption simply makes good common as well as supernatural sense, with this prayer to God: “You would not allow decay to touch her body, for she had given birth to your Son, the Lord of all life, in the glory of the incarnation.”

Have you ever received devastating news about a loved one? News that was so unbelievable at the time that it didn’t even register with you for a few moments, or even much longer?

Have you ever received devastating news about a loved one? News that was so unbelievable at the time that it didn’t even register with you for a few moments, or even much longer?

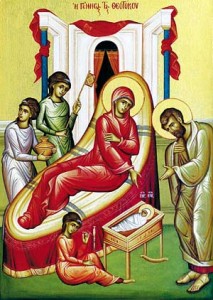

Today the Church celebrates the feast of the birth of Mary of Nazareth. Saint Peter Damian captured the elation Christians should feel on this day: “Just as Solomon and the chosen people celebrated the dedication of the Temple with great and solemn sacrifice, so should we be filled with joy at the birth of Mary. Her womb was a most holy temple. There, God received his human nature and thus entered visibly into the world” (Sermon 45).

Today the Church celebrates the feast of the birth of Mary of Nazareth. Saint Peter Damian captured the elation Christians should feel on this day: “Just as Solomon and the chosen people celebrated the dedication of the Temple with great and solemn sacrifice, so should we be filled with joy at the birth of Mary. Her womb was a most holy temple. There, God received his human nature and thus entered visibly into the world” (Sermon 45).