The old joke is still funny: Why did Peter deny Jesus? Peter was still mad that Jesus healed his mother-in-law. All kidding aside, many non-Catholics look at the indisputable fact that Peter had a mother-in-law (who was indeed healed by Jesus in Mark 1:30-31), and therefore must have had a wife, and consider the Catholic practice of clerical celibacy – well, a bad joke. They ask, “How can the Catholic Church require priestly celibacy when it’s clear that at least Peter – and possibly other Apostles – were married?”

The old joke is still funny: Why did Peter deny Jesus? Peter was still mad that Jesus healed his mother-in-law. All kidding aside, many non-Catholics look at the indisputable fact that Peter had a mother-in-law (who was indeed healed by Jesus in Mark 1:30-31), and therefore must have had a wife, and consider the Catholic practice of clerical celibacy – well, a bad joke. They ask, “How can the Catholic Church require priestly celibacy when it’s clear that at least Peter – and possibly other Apostles – were married?”

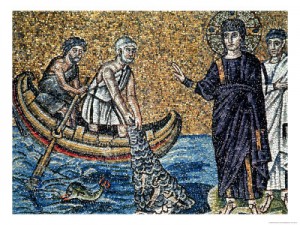

Today’s Gospel sheds light on both the Catholic practice in general, and Peter’s particulars. This is good evidence that Jesus himself required his apostles to share his way of life:

Peter began to say to Jesus,

‘We have given up everything and followed you.”

Jesus said, “Amen, I say to you,

there is no one who has given up house or brothers or sisters

or mother or father or children or lands

for my sake and for the sake of the Gospel

who will not receive a hundred times more now in this present age:

houses and brothers and sisters

and mothers and children and lands,

with persecutions, and eternal life in the age to come.

But many that are first will be last, and the last will be first.”

– Mark 10:28-31

The fact of the matter is that many clerics were ordained as married men in the early Church, but here’s the thing: they were required to be continent (abstain from marital relations) after ordination. There’s plenty of evidence that this practice dates to the Apostolic age and continued in both East and West. Strong documentation is found in Christian Cochini’s The Apostolic Origins of Priestly Celibacy, and Stefan Heid’s Celibacy in the Early Church, both published by Ignatius Press. Wives of potential clerics had to agree to such a change, or the ordination could not be carried out.

Peter, as Jesus indicated, left his wife and family home behind to follow Jesus more closely, as the Apostolic band roamed the countryside of Galilee. But this did not in any way indicate that he cruelly abandoned his bride, if she was indeed still living at the time. The extended family unit was paramount in Eastern cultures of the time, as it still is in many cases today. Many family members would often live under the same roof, and Mark notes that the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law occurred at Peter’s home in Capernaum. Peter’s wife would have been cared for. It is hardly imaginable that Jesus, who so despised divorce (which left women in a very precarious economic predicament in those days), would have advocated a cold dismissal of one’s spouse in order to be an Apostle.

Recently, the prominent canon lawyer Edward Peters has argued that the Church should return to her historical roots and that all clerics in higher orders, including permanent deacons (who currently are not required to do this), should observe the ancient practice of clerical continence. You can read his take here.

This is very interesting. I did not know about the rule of clerical continence. I dare say few people really do. There are also proofs within the Bible itself from Old Testament times that God was pleased by and demanded chastity, where the Levitical priesthood would have to abstain from sexual relations before serving before the Holy of Holies, or else they would be unclean. Then there is the part from 1 Samuel I believe where David and his men while fleeing from Saul hid in the temple where the Ark of the Lord was and the only thing they could eat was the bread offerings. Normally this is only reserved for the Levite priests, but due to the circumstances the Levite there saw the need to put aside ritual to serve the more immediate needs and asked David if he and his men had been chaste. That was their only requirement. Since they were, being soldiers carrying out Holy War and observed celibate discipline, they could eat the bread. Today priests hold in their hands something of far more value than the bread offering or the Ark of the Covenant, they hold and consecrate the Body of Christ itself in the Eucharist, and they do so everyday. So how much more need then is it that they too remain chaste everyday. This is a reality that is lost these days where unnecessary abuse of the priveledges of Eucharistic Ministers and Communion in the hand have taken away the special role of the Priest and his connection to the importance of the Eucharist, and so too it will undermine people’s thoughts about the need for celibacy when ministering to the Lord.

An intriguing qtsueion, this. Lora is quite right: celibacy did not become compulsory for priests until the 11th or 12th century but there was increasing expectation and pressure for celibacy bfore that. Certainly the tradition of celibacy does not go back right to the very beginning.But that doesn’t answer the qtsueion: was there a distinction in the earliest church between ordination after marriage or before it? I have no hard answers, but I will share two observations from my reading. First, although I have often come across the observation of the rule applying to the Eastern Church, I have never seen even a mention of it for the West. This would seem to suggest that there was no such rule.Second,in the very earliest church, there cannot have been a ban on marriage after ordination, for the simple reason that there was no practice of formal ordination. The institution of the priesthood as a distinct class within the church did not evolve until some time after deacons, bishops and finally presbyters who became the priests, I think in about the 4th C.On the other hand, I have never seen any reference to when the distinction of the order began in the Eastern Church and in the very earliest years, there was not the sharp contrast between East and West that emerged after the division of the Empire. The qtsueion intrigues me. I have a strong interest in the whole qtsueion of compulsory celibacy. If I learn anything in my further reading, I will let you know.,